Mean Pooling Beats Attention: Predicting Telomerase Activity from Whole-Slide Images

From global signals to local clues with ABMIL—and what it taught us about telomerase as a tissue-wide phenotype.

Introduction

In the first two posts (post-1, post-2) of this series, we built the biological and technical foundations of the project. We started by revisiting the role of telomerase in cancer and why its reactivation is central to unlimited cell division. We then assembled a reproducible multimodal dataset combining RNA-seq–derived telomerase labels with whole-slide histology images (WSIs) from TCGA, and showed that a simple image-based baseline already captures meaningful signal.

In this third post, we take the next conceptual step: instead of treating each slide as a single global object, we attempt to learn from the thousands of image patches that compose a WSI. Our original motivation is straightforward: if telomerase activity leaves a morphological footprint, where in the tissue does this signal come from?

To answer this, we turn to Attention-Based Multiple-Instance Learning (ABMIL), a framework designed precisely for weakly supervised problems like digital pathology. Along the way, however, we encounter an unexpected and instructive result: a simple global aggregation model outperforms ABMIL. Far from being a failure, this outcome teaches us something important about the biology of telomerase and the structure of the learning problem.

1. Why Multiple-Instance Learning for Histology?

Whole-slide images are enormous. A single WSI can contain hundreds of thousands of patches, each capturing a tiny region of tissue. Yet our supervision signal—TERT expression measured by RNA-seq—exists only at the slide (or patient) level. We do not know which patches are relevant, only that somewhere in the slide there may be visual correlates of telomerase activity.

This mismatch between many local inputs and one global label is a textbook case for Multiple-Instance Learning (MIL):

- A bag corresponds to one slide.

- Instances correspond to patches.

- The bag has a label, but the instances do not.

In classical MIL settings, a positive bag is assumed to contain at least one informative instance. In pathology, this might correspond to a small tumor focus or a rare cell population.

2. Attention-Based MIL: Learning to Focus

ABMIL extends this idea by replacing hard instance selection with a learned attention mechanism. Instead of deciding which patch matters in advance, the model learns a weight for each patch and computes a weighted average of patch embeddings to form a slide-level representation.

Conceptually, the pipeline looks like this:

- Each WSI is tiled into patches and converted into high-dimensional embeddings using a pretrained vision model (UNI in our case).

- A small neural network maps each patch embedding to an attention score.

- Attention scores are normalized across the slide.

- The slide embedding is computed as a weighted sum of patch embeddings.

- A classifier predicts whether the slide is telomerase-high or not.

This architecture is appealing for two reasons:

- It can, in principle, ignore irrelevant regions such as background or necrosis.

- It produces attention maps that can be visualized, offering interpretability.

At this stage, ABMIL seems perfectly suited to our goal of localizing telomerase-related morphology.

3. Practical Challenges in Training ABMIL

When we trained ABMIL on the full dataset, several challenges emerged.

First, overfitting appeared quickly. Training loss decreased steadily, but test loss often increased, and performance metrics plateaued. This was mitigated through a combination of:

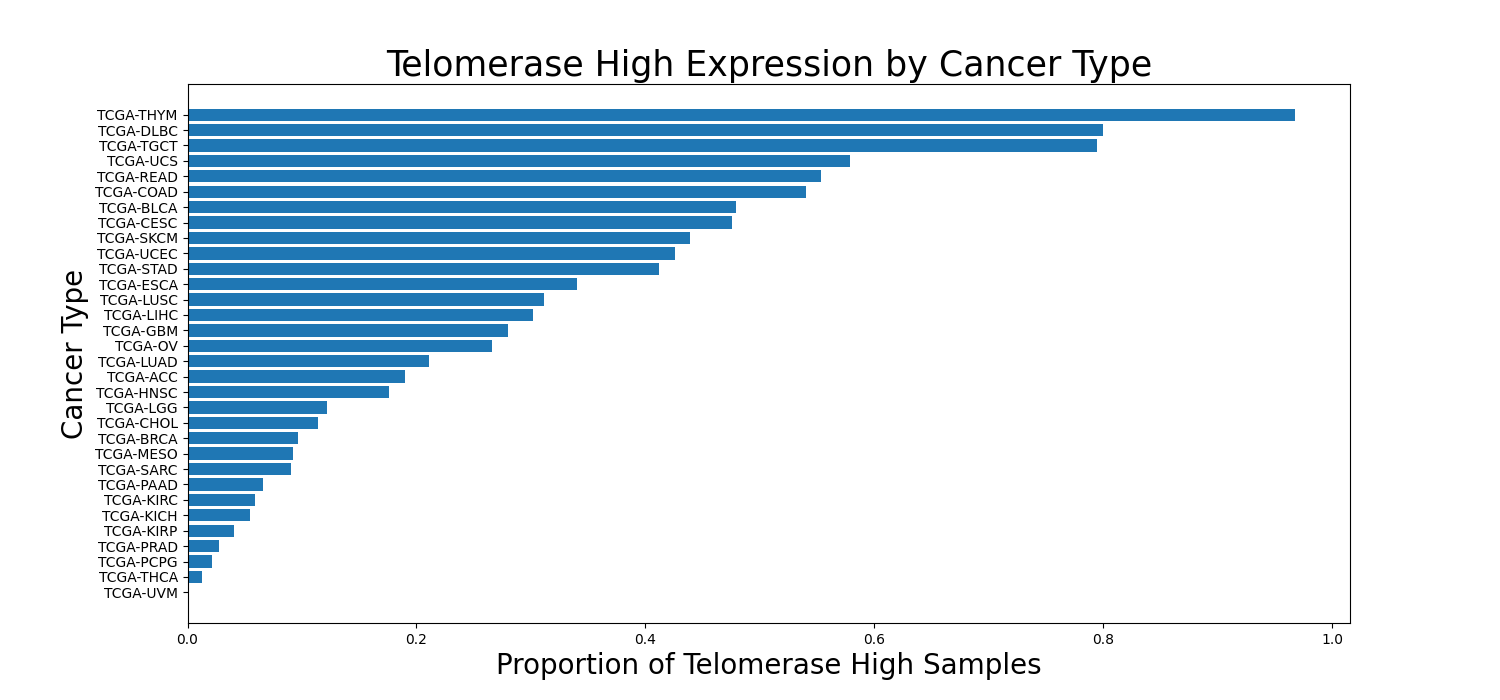

- redefinition of telomerase high labels per cohort to avoid class imbalance (cf Figure 1)

- strict patient-level splits to avoid leakage (in the code below,

case_barcodeuniquely identifies a patient)

# 1. patient-level table

df_cases = df_labels[['case_barcode', 'telomerase_high']].drop_duplicates()

skf = StratifiedKFold(n_splits=nb_folds, shuffle=True, random_state=42)

case_folds = {}

for i, (train_idx, test_idx) in enumerate(skf.split(df_cases, df_cases['telomerase_high'])):

case_folds[i] = {

"train_cases": set(df_cases.iloc[train_idx]['case_barcode']),

"test_cases": set(df_cases.iloc[test_idx]['case_barcode'])

}

# 2. Start from slide-level df_splits

df_splits = df_wsi_emb_labels[['project_short_name','case_barcode',

'sample_barcode', 'slide_barcode', 'AppMag',

'telomerase_high']].drop_duplicates().reset_index(drop=True)

for i in range(nb_folds):

col = f"fold_{i}"

df_splits[col] = None

df_splits.loc[df_splits['case_barcode'].isin(case_folds[i]['train_cases']), col] = 'train'

df_splits.loc[df_splits['case_barcode'].isin(case_folds[i]['test_cases']), col] = 'test'

- reduced model capacity by adding a bottleneck layer 1536 -> 128 -> 32

- strong regularization,

- and careful patch sampling.

Second, we observed that not all patches are equally informative. Many patches correspond to background or visually homogeneous tissue. To improve the signal-to-noise ratio, we introduced a simple heuristic: select patches with high embedding variance, then sample from this subset during training. This stabilised training and improved performance.

k = 4096 # kept patches with highest features variance

num_features = 1024 # randomly sample 1024 patches among the 4096 high variance features patches

scores = features.var(dim=1)

topk_indices_sampled = torch.topk(scores, k).indices

# sample randomly among high variance feature patches

topk_indices_sampled = torch.randperm(k)[:num_features]

features = features[topk_indices_sampled]

With these refinements, ABMIL reached respectable results, confirming that the model was indeed extracting meaningful signal from histology.

4. A Strong Baseline

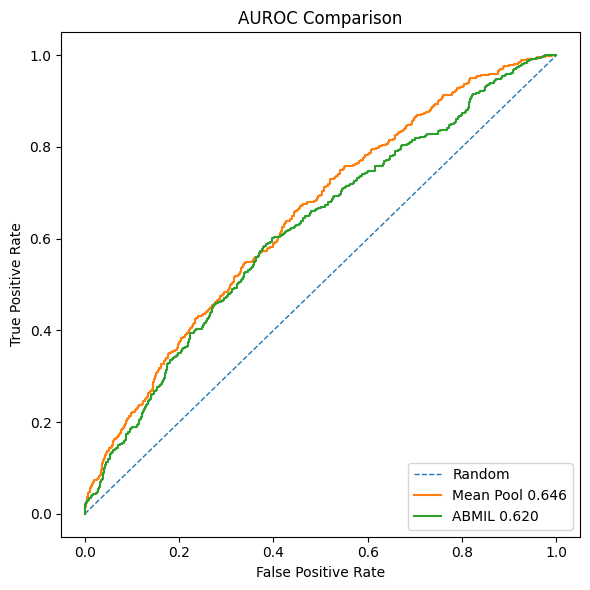

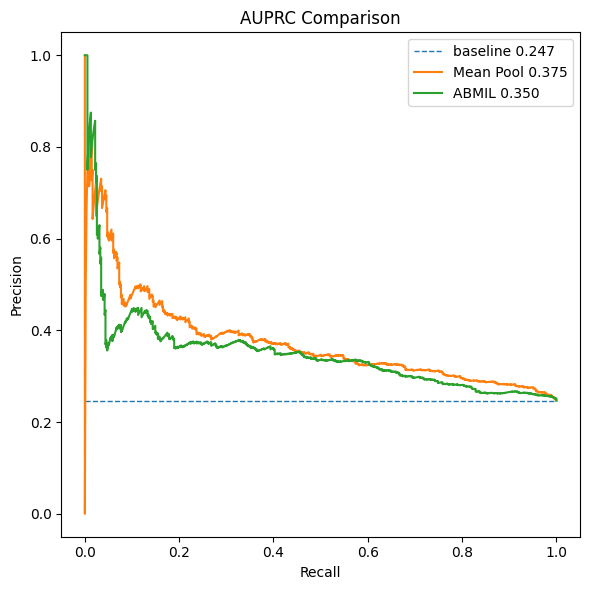

At the end of Post 2, we introduced a baseline method: mean pooling of patch embeddings, followed by a standard multilayer perceptron. Surprisingly, this simple approach consistently outperformed ABMIL:

- Higher AUROC

- Higher AUPRC

- Faster convergence

- Greater training stability

This result forces us to pause and reassess our assumptions.

5. Why Does Mean Pooling Work Better?

The answer lies in the biological nature of telomerase activity and the type of supervision available.

5.1 Telomerase as a Global Phenotype

Telomerase activation is not a rare, focal event like a micrometastasis. It is tightly linked to global tumor properties such as:

- proliferation rate,

- cellular density,

- nuclear atypia,

- genomic instability.

These features tend to be distributed across large regions of the tumor, not confined to a small subset of patches. As a result, many patches carry weak but consistent information related to telomerase status.

Mean pooling aggregates this diffuse signal effectively:

- noise averages out,

- shared structure is reinforced,

- and the resulting representation aligns well with slide-level RNA measurements.

5.2 Weak Supervision Favors Simplicity

Our labels are derived from RNA-seq and thresholded at the cohort level. They are inherently noisy and provide no spatial guidance. Under such weak supervision, ABMIL is forced to assign meaning to individual patches without ground truth, increasing the risk of focusing on spurious correlations.

Mean pooling makes a much weaker assumption: all patches contribute partial evidence. In this context, that assumption turns out to be better aligned with reality.

5.3 Optimization Matters

Finally, the mean-pooling model is simply easier to train. It operates on one vector per slide, has smoother gradients, and avoids the instability introduced by attention normalization over thousands of instances. When the signal is global, this simplicity becomes an advantage rather than a limitation.

6. What This Result Tells Us

The takeaway is not that ABMIL is ineffective, but that the problem itself is not strongly instance-driven. Telomerase-associated morphology appears to be a global tissue phenotype, and global aggregation provides a better inductive bias.

ABMIL remains valuable for:

- interpretability,

- exploratory analysis,

- tasks driven by localized signals,

- and potentially as a second-stage refinement model.

But for the core prediction task, mean pooling captures the dominant signal more efficiently.

Lessons Learned

-

Not every WSI problem is a multiple-instance problem. Although WSIs are composed of many patches, the predictive signal may still be global rather than localized.

-

Biology determines the right inductive bias. Telomerase activity reflects widespread tumor properties (proliferation, cellularity, nuclear atypia), making global aggregation more effective than patch selection.

-

Weak supervision favors simpler aggregation. When labels come from slide-level RNA measurements, enforcing instance-level explanations can amplify noise instead of reducing it.

-

Attention is a tool, not a guarantee. Attention-based MIL provides interpretability and is powerful for focal phenomena, but it is not universally superior to simpler pooling strategies.

-

Strong baselines are essential. Comparing against a simple mean-pooling model was crucial to correctly interpret ABMIL’s behavior and avoid overfitting the modeling approach to the data.

Conclusion

Across these three posts, we set out to explore whether telomerase activity—a fundamentally molecular property—leaves a detectable imprint in tumor histology.

We began by grounding the problem in cancer biology, then built a multimodal dataset linking RNA-seq–derived telomerase labels to whole-slide images. Finally, we explored increasingly structured models, from global pooling to attention-based multiple-instance learning.

The most important result is not a particular metric, but a conceptual one: telomerase-associated morphology appears to be predominantly global rather than focal. In this regime, simple aggregation strategies outperform more complex instance-selection mechanisms, especially under weak supervision.

This outcome reinforces a broader lesson in applied machine learning for biology: architectural sophistication must follow biological structure, not precede it. Attention-based models remain invaluable tools—but only when the underlying signal truly demands them.

With this, we close the series having not only improved performance, but also gained a clearer understanding of how telomerase activity manifests in histological space.