Understanding Cancer and Telomerase: From Biology to New Treatments

Part-1 in a series of posts about proteomics, cancer biology, and AI-driven solutions for oncology.

This article is the first in a series of posts where I share my journey exploring proteomics, cancer biology, and AI-driven solutions for oncology. In the upcoming posts, I will expand on the data foundations of the project, the machine learning methods we are testing, and the clinical implications of this research. The goal of the series is to make complex concepts accessible while also showing the step-by-step progress of building an applied research project from biology to artificial intelligence. Stay tuned if you are curious about how molecular data, medical images, and deep learning can come together to address one of the most fundamental challenges in cancer research. The follow-up post to this is Post 2

Introduction

What Is Cancer and How Does It Start?

Cancer is not a single disease but rather a broad category of disorders in which cells grow and divide uncontrollably. In healthy tissues, cells follow a highly regulated cycle: they grow, divide when necessary, and eventually die through a process called apoptosis, often described as “programmed cell death.” This cycle ensures balance—old or damaged cells are removed, and new cells take their place. In cancer, this balance is lost. Cells accumulate mutations in their DNA that alter key instructions, causing them to ignore normal stop signals. Instead of halting growth, they continue dividing even when the body does not need them. Over time, these uncontrolled divisions lead to the formation of tumors, which can invade surrounding tissues and disrupt organ function. In advanced stages, cancer cells can spread through the bloodstream or lymphatic system to distant parts of the body, a process known as metastasis, which makes cancer especially life-threatening.

What Are the “Hallmarks of Cancer”? (Hanahan and Weinberg Explained)

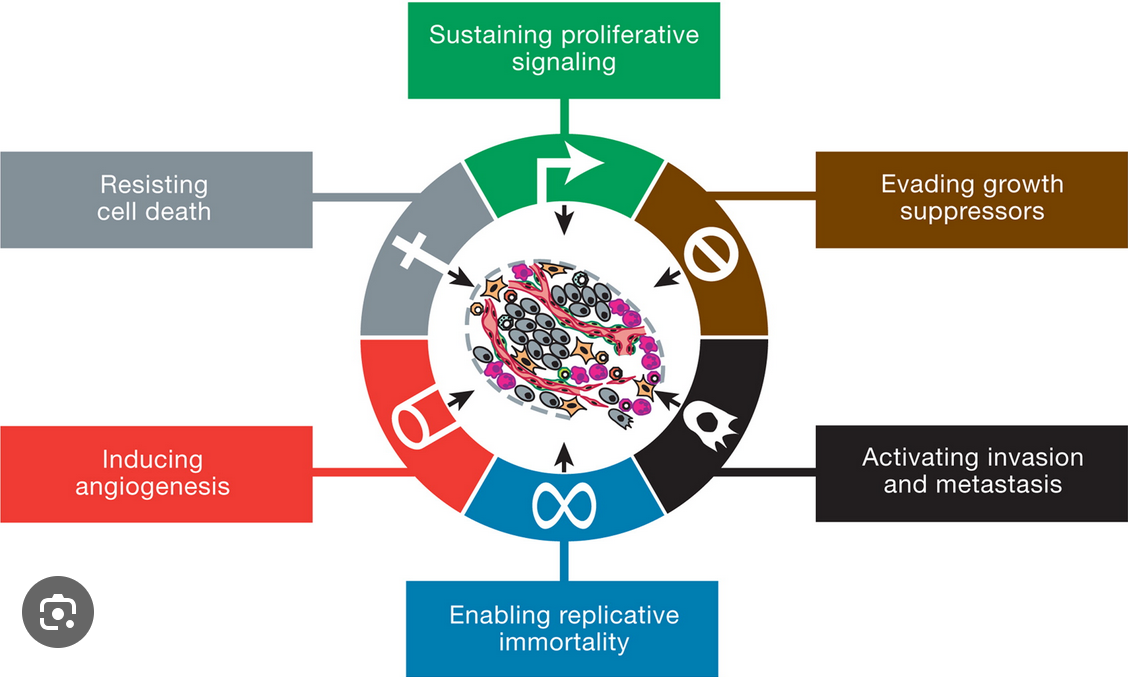

In 2000, scientists Douglas Hanahan and Robert Weinberg proposed a groundbreaking framework known as the “Hallmarks of Cancer”, published in the journal Cell. These hallmarks describe the common strategies cancer cells adopt to survive, proliferate, and spread, despite being fundamentally abnormal. The original six hallmarks include:

-

Sustaining proliferative signaling: Cancer cells constantly send themselves signals to keep dividing.

-

Evading growth suppressors: They ignore instructions from the body that would normally stop cell division.

-

Resisting cell death: They avoid apoptosis, living far longer than normal cells.

-

Enabling replicative immortality: They find ways to divide endlessly, escaping the natural aging of cells.

-

Inducing angiogenesis: They stimulate the formation of new blood vessels to secure nutrients and oxygen.

-

Activating invasion and metastasis: They acquire the ability to move into surrounding tissues and spread throughout the body.

In 2011, Hanahan and Weinberg updated their model to include additional hallmarks, such as reprogramming cellular metabolism to fuel rapid growth and evading immune destruction to avoid being eliminated by the body’s defenses [Hanahan & Weinberg, 2011]. Together, these hallmarks provide a unifying explanation of how diverse cancers share fundamental biological traits.

What Does “Unlimited Replicative Potential” Mean in Cancer?

One particularly striking hallmark is unlimited replicative potential, sometimes described as “cellular immortality.” Normal cells cannot divide forever. Each cell has a built-in counter that limits how many times it can replicate, after which it enters senescence (a state of permanent rest) or undergoes apoptosis. This limit prevents damaged or aged cells from accumulating. Cancer cells, however, bypass this limit. By doing so, they can continue dividing indefinitely, producing thousands or millions of offspring cells that form the bulk of a tumor. This ability is made possible through molecular tricks that preserve the cell’s genetic stability, the most important of which involves maintaining the telomeres—the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes. Without this adaptation, cancer cells would quickly exhaust their ability to divide and stop growing. Thus, unlimited replicative potential is not just a curious trait—it is one of the central reasons cancer can persist and expand in the body.

How Do Cancer Cells Keep Dividing Forever?

What Are Telomeres and Why Are They Important?

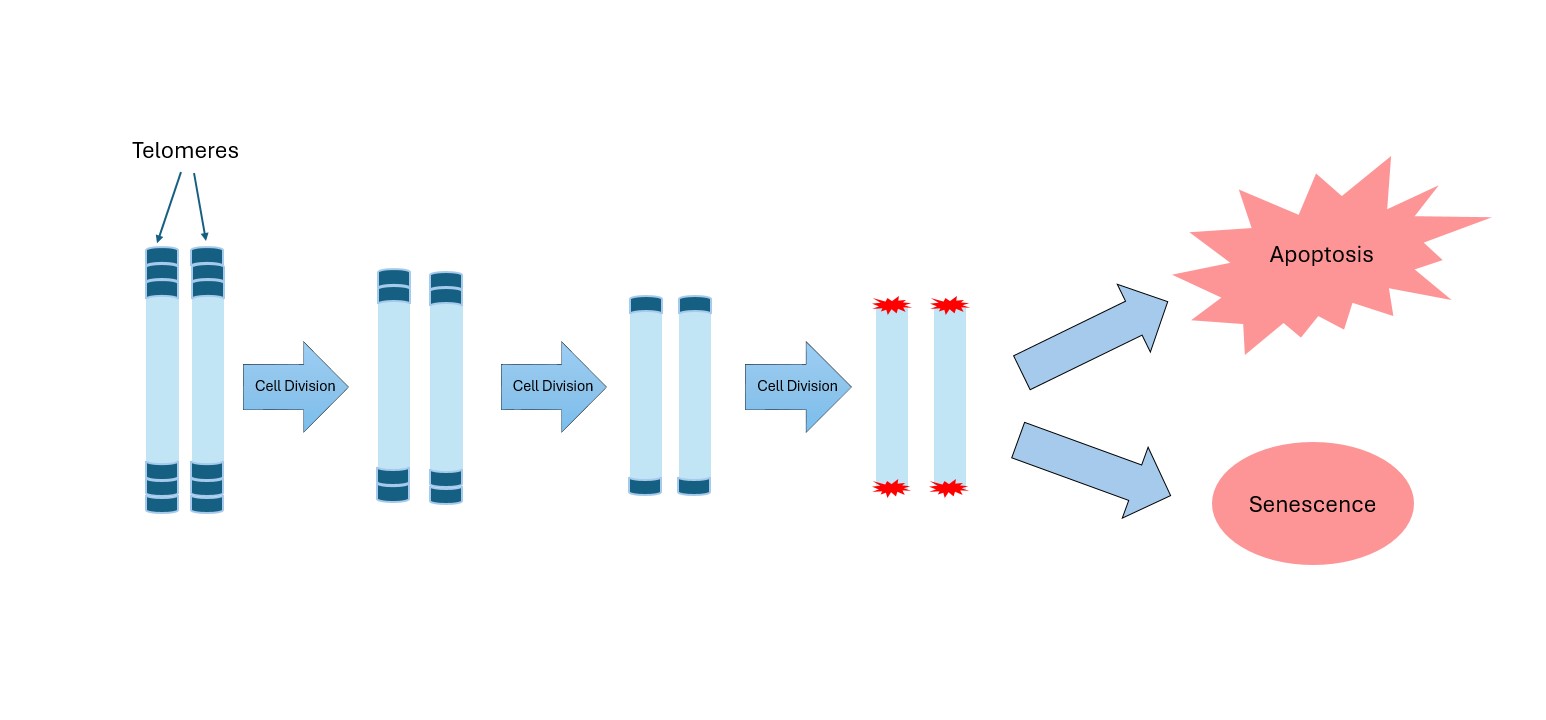

Telomeres are repetitive DNA sequences located at the ends of chromosomes, serving as protective caps that safeguard genetic material. Imagine the small plastic tips at the ends of shoelaces—without them, shoelaces fray and eventually become unusable. Telomeres perform a similar function: they prevent chromosomes from “fraying” or fusing with each other, which would cause serious genetic errors. Every time a cell divides, its telomeres become slightly shorter, because DNA replication machinery cannot fully copy the ends of chromosomes. This gradual shortening acts as a biological clock, limiting the number of times a cell can divide. Once telomeres reach a critically short length, the cell is signaled to stop dividing, entering senescence or apoptosis. This safeguard protects organisms from uncontrolled cell growth, as it prevents damaged or mutated cells from replicating indefinitely. However, cancer cells find ways to bypass this system, largely by reactivating an enzyme called telomerase.

What Is Telomerase and What Does It Do?

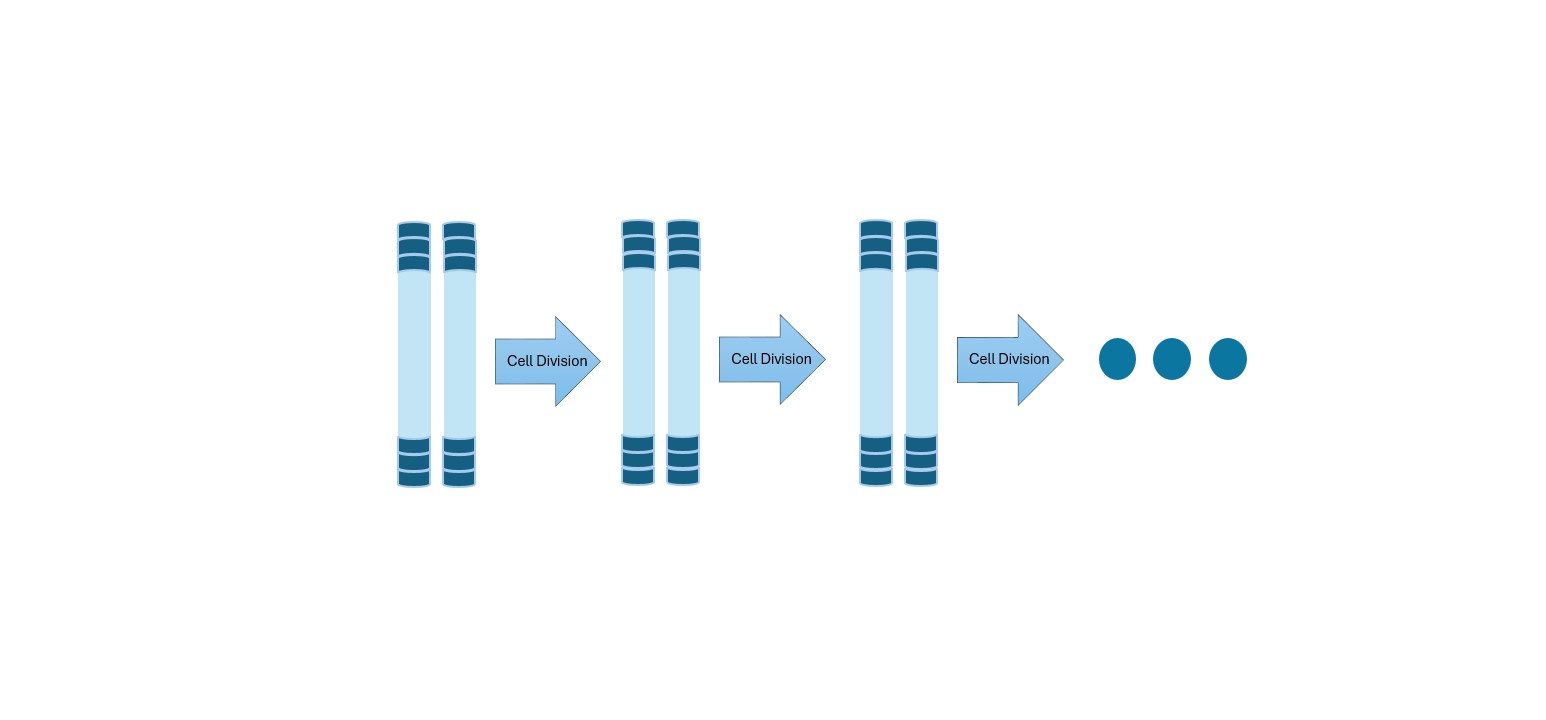

Telomerase is an enzyme that helps maintain the length of telomeres. It does this by adding back short DNA repeats to chromosome ends, counteracting the natural shortening that occurs during cell division. Telomerase is composed of two main parts: a protein component that acts as the “engine” and an RNA component that provides the template for adding DNA sequences. In most adult cells, telomerase is inactive or present only at very low levels. This ensures that cells do not divide endlessly. However, in certain cell types, such as stem cells (which need to produce new cells throughout life) and germ cells (sperm and egg cells), telomerase remains active to preserve their long-term function. In cancer cells, telomerase is almost always reactivated, allowing these cells to stabilize their telomeres and divide indefinitely. This makes telomerase one of the key tools cancer cells use to achieve replicative immortality.

How Are Telomeres and Telomerase Linked to Cancer?

The relationship between telomeres, telomerase, and cancer is central to understanding how tumors can grow without limit. In normal cells, telomere shortening acts as a defense mechanism against uncontrolled growth. It ensures that even if cells acquire mutations, their division potential is finite. Once telomeres reach a critically short length, DNA damage signals are triggered, leading the cell into senescence or apoptosis. This is sometimes called the “Hayflick limit”, named after the scientist who first described it in the 1960s.

Cancer cells, however, find ways to escape this limit. The most common strategy, observed in about 85–90% of human cancers, is reactivation of telomerase [Shay & Wright, 2019]. By restoring telomere length, cancer cells can divide indefinitely, effectively sidestepping one of the body’s key anticancer mechanisms. This reactivation is not random—mutations in the TERT gene (which encodes the catalytic subunit of telomerase) have been identified in many cancers, particularly in brain tumors, liver cancer, and melanoma.

In the remaining cancers (~10–15%), cells use alternative mechanisms collectively known as ALT (Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres), which rely on recombination-based processes to maintain telomeres without telomerase. While less common, ALT still allows cancer cells to achieve replicative immortality.

Ultimately, by maintaining their telomeres through telomerase or ALT, cancer cells remove one of the biggest barriers to endless growth. This is why targeting telomerase has become such an appealing therapeutic strategy: inhibiting it could theoretically strip cancer cells of their immortality, forcing them to age and die like normal cells.

Can We Treat Cancer by Targeting Telomerase?

How Common Is Telomerase Reactivation Across Cancer Types?

Telomerase reactivation is widespread: roughly 90% of solid tumors and ~85% of blood cancers show elevated activity [Shay & Wright, 2019], including lung, breast, prostate, pancreatic, colorectal, glioblastoma, and liver cancers. Because most normal cells don’t depend on telomerase, it’s an attractive, relatively selective target—though safety is nuanced since some stem cells require it.

Imetelstat: The First FDA-Approved Telomerase Inhibitor (2024)

In 2024, the FDA approved Imetelstat, a first-in-class oligonucleotide that binds telomerase RNA and blocks telomere extension. Approved for myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), trials showed meaningful benefit and proved that telomerase inhibition works in humans, spurring exploration in other cancers.

What’s Next? New Research on Telomerase Inhibitors in Cancer

Since the approval of Imetelstat, there has been a surge of interest in expanding the scope of telomerase-targeted therapies. Several ongoing clinical trials are evaluating its efficacy beyond MDS. For instance, studies in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) have shown that Imetelstat can reduce the number of malignant stem cells, which are often resistant to conventional chemotherapy. Other trials are testing its role in essential thrombocythemia (ET) and myelofibrosis, diseases characterized by abnormal blood cell production.

In the realm of solid tumors, research is more complex. Tumor cells often exist in diverse microenvironments and may rely on additional survival pathways beyond telomerase. Nonetheless, preclinical models have demonstrated promising results in cancers such as breast, lung, and ovarian cancers, where telomerase inhibitors appear to slow tumor growth when combined with existing therapies like chemotherapy or immunotherapy.

Another promising area involves combination strategies. Because some cancers rely on the alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) pathway, researchers are investigating whether blocking telomerase in combination with DNA-damaging agents or checkpoint inhibitors could produce more durable responses. There is also growing interest in developing next-generation telomerase inhibitors with improved specificity and fewer side effects compared to Imetelstat.

While challenges remain—particularly in balancing safety, effectiveness, and long-term outcomes—the progress made in the past few years highlights a growing consensus: telomerase inhibition has moved from a theoretical concept to a practical therapeutic approach. As clinical research advances, telomerase inhibitors could become a valuable addition to the oncologist’s toolkit, especially for cancers that currently lack effective treatments.

How Do Scientists Measure Telomerase Activity?

Cell Differentiation and Tools to Track Telomerase (RNA-seq and Proteomics)

To understand why and how telomerase becomes reactivated in cancer, it is useful to revisit the concept of cell differentiation. Differentiation is the process by which immature cells develop into specialized types, such as muscle cells, neurons, or blood cells. As cells differentiate, they generally lose telomerase activity, committing to a finite lifespan. In contrast, stem cells and certain progenitor cells maintain telomerase activity to support tissue regeneration.

Measuring telomerase activity is therefore crucial in both research and clinical settings. Two of the most widely used approaches are RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and proteomics.

-

RNA sequencing: This method measures the abundance of RNA molecules, including those encoding telomerase components. RNA-seq can provide quantitative insights into gene expression patterns, helping researchers identify whether telomerase-related genes are turned on or off in different cell populations.

-

Proteomics: Since proteins are the functional molecules in cells, proteomics offers a more direct measure of telomerase activity. By analyzing the proteins expressed in a sample, researchers can detect the presence and levels of telomerase subunits, giving a clearer picture of its functional status.

Together, these techniques have been instrumental in revealing how telomerase is controlled across different stages of cell differentiation and how its dysregulation contributes to cancer.

What Are the Limitations of Current Telomerase Monitoring Methods?

Despite their importance, current methods for measuring telomerase activity have significant limitations. RNA sequencing provides valuable molecular detail, but it lacks spatial resolution. This means that while we may know how much telomerase RNA is present in a tumor sample, we cannot determine exactly where within the tissue telomerase is active. Tumors are highly heterogeneous—different regions may behave very differently—so knowing the precise location of telomerase activity could be critical for diagnosis and treatment.

Proteomics, on the other hand, offers a way to examine proteins in their tissue context, sometimes capturing spatial differences. However, it remains costly and technically demanding. High-quality proteomic analysis requires advanced equipment, significant expertise, and often large amounts of biological material. This makes it difficult to apply routinely in clinical practice, where time and cost are major considerations.

Because of these challenges, there is a growing demand for innovative approaches that can combine the molecular precision of RNA-seq with the spatial insights of proteomics, but at a scale and cost suitable for real-world use. Bridging this gap could revolutionize how we study telomerase and open new avenues for tailoring cancer therapies.

New AI-Based Solution

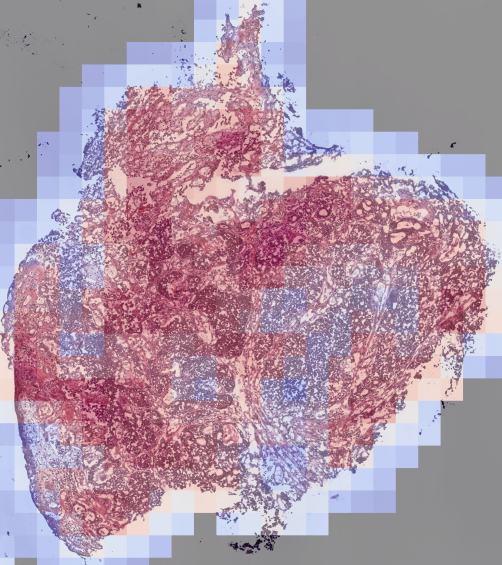

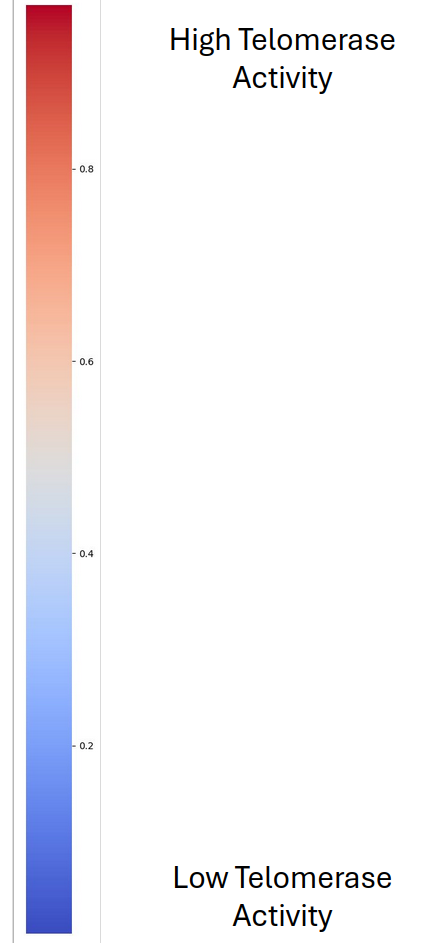

Can Deep Learning Predict Where Telomerase Is Active in Tumors?

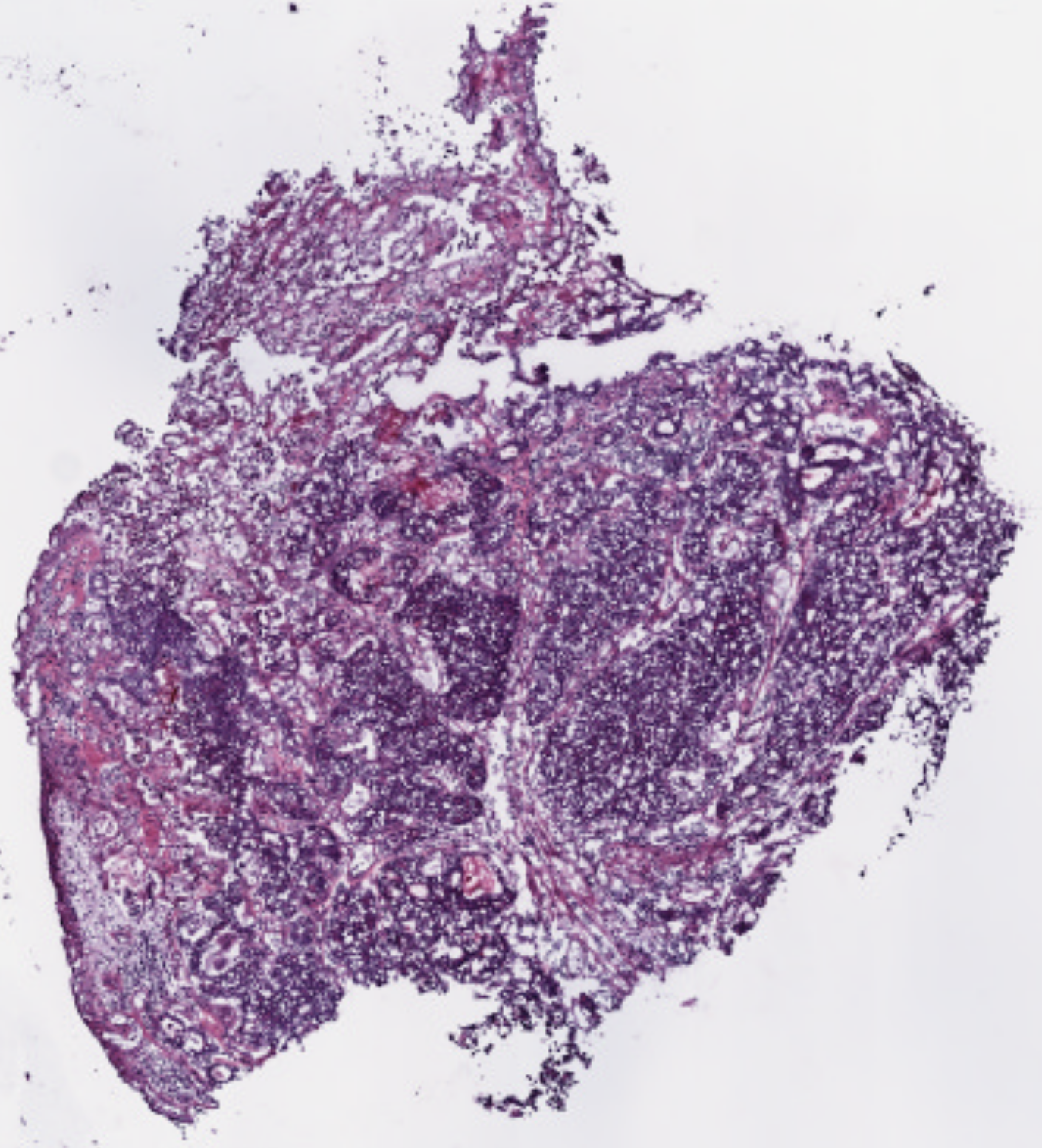

A promising future solution lies in applying deep learning, a branch of artificial intelligence, to medical imaging. In cancer diagnostics, one of the most common tools is the Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain, used to prepare tissue biopsies. These stained slides are examined under a microscope by pathologists to identify cancerous features. While traditionally interpreted by human experts, H&E slides also contain subtle visual cues that correlate with underlying molecular processes, including protein activity.

Proteins, including those linked to telomerase, influence the structure and appearance of tissues at the microscopic level. Deep learning models can be trained on large datasets of biopsies to recognize these patterns, even when they are invisible to the human eye. By linking image features with known measures of telomerase activity, the AI system could learn to generate heatmaps—color-coded overlays highlighting regions within the biopsy where telomerase is most active.

This approach has several advantages. First, it leverages existing biopsy material, meaning no additional invasive procedures are required. Second, it provides spatially resolved information about telomerase activity, addressing a major limitation of current molecular techniques. Finally, once trained, the model could produce results rapidly and at relatively low cost, making it practical for both research laboratories and clinical settings.

How Could Clinicians Use AI to Guide Cancer Treatment and Drug Discovery?

If successfully developed, such AI-based tools could transform cancer care in several important ways. For clinicians, the ability to map telomerase activity within tumors would enable more personalized treatment decisions. For example, if a patient’s biopsy shows high levels of telomerase activity, the oncologist might consider prescribing a telomerase inhibitor like Imetelstat. Conversely, if telomerase is low or absent, other therapeutic options could be prioritized.

Beyond patient selection, this method could also be used to monitor treatment effectiveness. Imagine a patient receiving a telomerase inhibitor: by analyzing biopsies taken before, during, and after treatment, clinicians could see whether telomerase activity decreases in response to the drug. This real-time feedback would allow them to adjust treatment strategies more quickly, improving patient outcomes.

The technology would also have significant implications for drug discovery and clinical research. Pharmaceutical companies developing new telomerase inhibitors could use AI-generated maps to assess how well their compounds work in preclinical models or clinical trials. Instead of relying solely on molecular assays, they would have spatial evidence of how telomerase activity changes within tumors, helping guide drug design and dosing strategies.

In the long term, integrating deep learning into cancer pathology could contribute to a broader movement toward precision oncology—a model of care in which therapies are tailored to the unique biological features of each patient’s tumor. By bridging molecular biology with digital pathology, spatial telomerase mapping could play a pivotal role in bringing this vision closer to reality.

In the next post, we move from biology to data. We will describe how telomerase activity can be operationalized as a learning target using RNA-seq, and how whole-slide histology images can be transformed into machine-learning–ready representations.

References:

Hanahan, D., & Weinberg, R. A. (2000). The Hallmarks of Cancer. Cell, 100(1), 57–70.

Hanahan, D., & Weinberg, R. A. (2011). Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell, 144(5), 646–674.

Shay, J. W., & Wright, W. E. (2019). Telomeres and Telomerase: Three Decades of Progress. Nature Reviews Genetics, 20, 299–309.