Building a Production Multi-Agent System for Document Writing

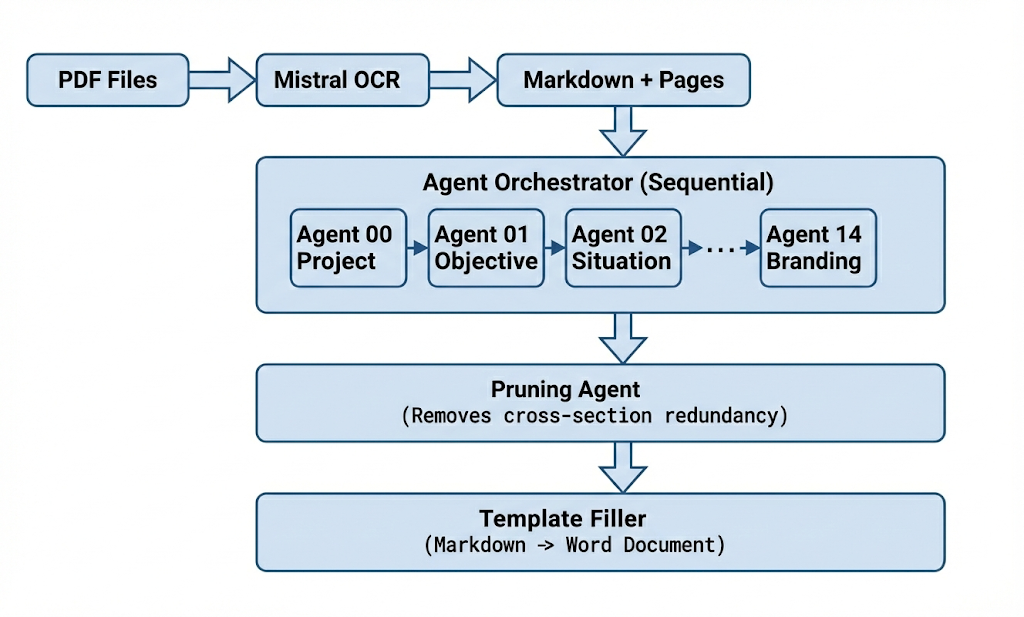

A deep dive into the architecture of a briefing generation system that uses 15 specialized AI agents to transform PDF source materials into structured documents.

Automating document generation from unstructured sources sounds straightforward until you try it. This post describes the architecture of a briefing generation system that takes PDF source materials and produces structured brief documents using 15 specialized AI agents.

A brief is a structured document that synthesizes scattered information into a single reference point. It typically includes sections like objectives, context, and deliverables. Writing a good brief requires both gathering relevant information from disparate sources—slide decks, strategy documents, meeting notes, research reports—and distilling it into clear, actionable prose.

The system processes PDF documents with complex layouts, tables, mixed content type and generates professional briefing sections. What makes this interesting is not the concept (multi-agent systems are well-documented) but the production trade-offs: where theoretical parallelism meets API rate limits, where agent autonomy meets output verification, and where flexibility meets maintainability.

PDF Processing: Why API-Based OCR

The first decision was how to extract content from PDFs. We evaluated three approaches: Marker (open-source PDF parser), Docling (IBM's document intelligence library), and Mistral's OCR API.

We chose Mistral OCR for deployment pragmatism. Running open-source models on a server requires managing container sizes, GPU allocation, and model versioning. An API call eliminates that operational surface area. The trade-off is external dependency, but for a system already dependent on LLM APIs, adding another doesn't materially change the reliability profile.

Mistral's document understanding handles the specific challenges of complex PDFs well: multi-column layouts and complex tables. The API returns structured markdown with preserved reading order, which matters when agents need to understand document flow rather than just extract keywords.

Compression Before Extraction

Large PDFs create latency and cost problems. Documents over 50MB go through a compression step: parallel image extraction using PyMUPDF, JPEG compression at 50% quality, and document reassembly. This typically achieves 70-80% size reduction.

The trade-off is image fidelity loss. But for briefing generation, we only need text content, not pixel-perfect images. OCR quality on compressed images remains acceptable because text rendering isn't affected by JPEG artifacts at this quality level.

Markdown as the Bridge

The system converts PDFs to markdown before agent processing. This intermediate format serves several purposes:

Debugging visibility. When an agent produces incorrect output, you can inspect the markdown it received. With direct PDF-to-agent pipelines, diagnosing whether the problem is extraction or reasoning becomes harder.

Page markers for citation tracking. The converted markdown includes HTML comments marking page boundaries (<!-- Page 1 -->). Agents embed citations in their output ([Source: filename.pdf, Page 3]), creating traceability from any claim back to source material.

Image removal. We strip image references from the markdown. Briefings are text documents; embedded images don't add value and would consume agent context windows without benefit.

Multi-Agent Orchestration

The system uses 15 specialized agents, each responsible for one brief section: project information, objectives, situation analysis, and so on. This decomposition reflects how briefings are actually structured—discrete sections with different concerns.

Configuration-Driven Agent Selection

Agent definitions live in a YAML configuration file:

agents:

briefing-objective-writer:

output_file: "01_objective.md"

prompt_file: "briefing-objective-writer.md"

briefing-situation-writer:

output_file: "02_situation.md"

prompt_file: "briefing-situation-writer.md"

# ... 13 more agents

This declarative approach means adding or modifying agents doesn't require code changes—edit the YAML, update the prompt file, and the orchestrator picks it up. The trade-off is managing 15+ prompt files. With that many agents, prompt drift and inconsistency become real concerns.

Not every agent runs for every job. Meeting briefings require logistics and format sections; creative concept briefings need insight sections, but skip the logistics section. The orchestrator filters agents based on the deliverable type at runtime. This is simpler than maintaining separate configuration files per deliverable, although it does mean that the filtering logic resides in code rather than configuration.

Sequential Execution of Agents

Sequential execution solves three problems:

Rate limit management. LLM APIs have rate limits. Firing 15 agents simultaneously risks hitting those limits and requires complex retry-with-backoff logic across concurrent requests.

Cost predictability. Sequential execution makes costs linear and predictable. Parallel execution with retries can create cost spikes that are hard to forecast.

Simpler debugging. When something fails, you know exactly which agent failed and in what order. Parallel failures create ambiguous states.

The trade-off is execution time. A full brief takes 10-15 minutes. For a batch processing system, this is acceptable. For real-time use cases, it would not be.

The Agentic Loop

Each agent operates within a tool-use loop. The agent receives a system prompt defining its role, access to tools (read_file, write_file, list_files, search_files), and a task prompt. It then iterates: read source materials, reason about content, write output.

for turn in range(1, MAX_TURNS + 1):

response = call_llm(messages, tools)

if response.is_complete:

break

if response.has_tool_calls:

for tool_call in response.tool_calls:

result = execute_tool(tool_call)

messages.append(tool_result(result))

The loop caps at 15 turns. This prevents runaway agents that keep calling tools without converging. In practice, most agents complete in 5-7 turns.

Agent Reliability: Trust But Verify

Here's something that surprised me: agents don't always follow instructions. An agent might reason correctly about the source material, generate appropriate content, and then simply not call the write_file tool. The conversation ends with "I've completed the analysis," but no output file exists.

This happens often enough that we built verification into the orchestrator. After each agent completes, the system checks whether the expected output file actually exists. If not, it retries with escalated instructions:

if not output_file.exists():

retry_prompt = """

CRITICAL: Your previous attempt did NOT write the output file.

You MUST use the write_file tool to save your output.

"""

run_agent_again(retry_prompt)

The system allows up to 3 attempts per agent. This verification layer adds API calls but prevents silent failures that would corrupt the entire brief.

The broader lesson: agent success (model says it's done) does not equal task completion (output actually exists). Production multi-agent systems need verification at every stage.

Post-Processing: The Pruning Pattern

With 15 agents writing independently, redundancy is inevitable.

We handle this through post-processing rather than prevention. A pruning agent runs after all sections are written, reading through the complete brief and removing duplicate information according to "section ownership" rules.

This approach has clear trade-offs. We're generating content that gets deleted—wasted tokens. But the alternative is inter-agent communication: each agent would need to know what previous agents wrote, creating complex dependencies and ordering requirements.

Independent agents with post-hoc cleanup is operationally simpler. Each agent can be developed, tested, and modified without considering its effect on other agents. The pruning agent is the only component that needs system-wide awareness.

Prompt Management

Prompts are the primary tuning mechanism. Getting a briefing section right requires iterating on the prompt—adjusting tone, adding constraints, and clarifying scope boundaries.

The system stores prompts in a PostgreSQL database with version history. The orchestrator checks for a custom prompt before falling back to the default file. This enables:

Runtime iteration. Update a prompt through the UI, and the next job uses it. No deployment required.

A/B testing. Run different prompt versions to compare output quality.

Rollback. If a prompt change degrades quality, revert to a previous version.

The trade-off is database dependency and UI complexity. For a simpler system, file-based prompts with git versioning would work. But when non-engineers need to iterate on prompts, a UI with version history becomes necessary.

Prompt Engineering Patterns

Several patterns emerged across the 15 agent prompts:

Explicit scope boundaries. Agents tend to over-explain. The writer prompt includes: "If you find yourself explaining market dynamics—STOP. That belongs in the Situation section."

Mandatory citations. Every paragraph must end with [Source: filename, Page X]. This is enforced through prompt language, not code validation. Agents follow this instruction reliably when it is prominent.

Hard length limits. "EXACTLY 1-2 sentences—NO EXCEPTIONS." Without explicit limits, agents produce verbose output. Even with limits, they sometimes exceed them, but the constraint improves average output length.

Conclusion

This architecture prioritizes debuggability, cost predictability, and operational flexibility over theoretical optimality. True parallel execution would be faster. Preventing redundancy during generation would use fewer tokens. Direct PDF-to-agent pipelines would have fewer moving parts.

But production systems operate under constraints that theoretical architectures ignore. Rate limits exist. Agents fail in unexpected ways. Non-engineers need to modify prompts. Documents need traceable citations.

The key insight from building this system: multi-agent architectures in production are primarily about managing complexity, not maximizing parallelism. Every architectural decision that adds flexibility also adds something to maintain, debug, and explain. The goal is finding the right trade-offs for your specific constraints—not building the theoretically optimal system.